Uh, excuse me. ✋ I’m Rafael from the future. I’ve come back in time to write about Tablecraft, and how it came about. Obviously, in the distant future from whence I came, everyone knows about Tablecraft and how it acquired Google for a trillion dollars, but here in the past no one has heard of it yet, which is very alarming. If no one hears about it now, the trillion dollar acquisition will never happen, I will never be a guest on Oprah’s new show and that homeless man to whom I gave a Lamborghini on live-stream will have to start walking again – and that’s NOT okay. So let’s get this PR campaign started.

Back in the Fall of 2017, I paired with 4 other wonderful people to put together a game in 2 weeks. After successfully convincing the rest of the team that we had to explore VR, we began brainstorming ideas for a VR game that could go beyond just entertainment, and eventually we started working on our brilliant VR game idea: VR camping simulator.

It was gonna be great. You were gonna learn how to tie knots in VR, and put together a tent and then learn how to throw your backpack on top of a tree so that bears can’t get to it, except – oh wait, that’s the most boring game of all times. 🤦♂️

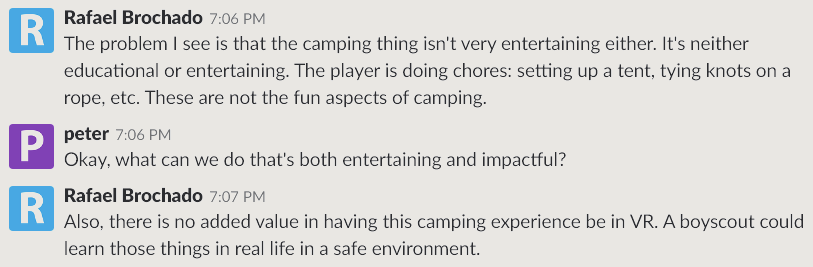

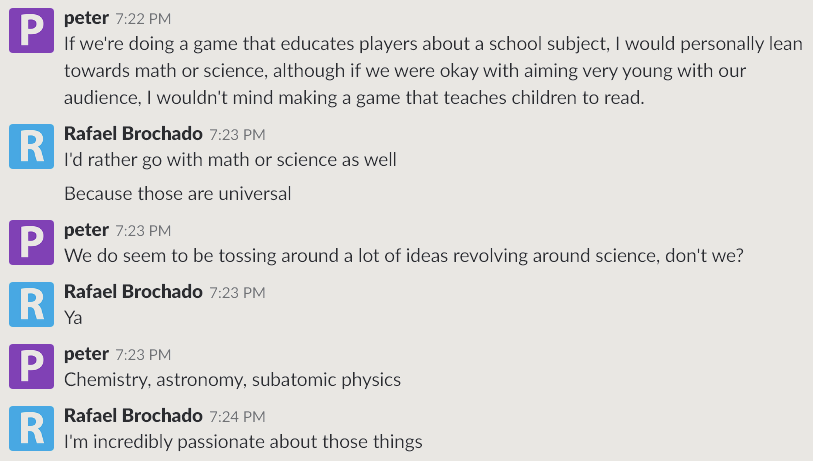

After we spent nearly a full week of development on that, we started to realize the idea wasn’t very inspiring, so I exposed my concerns to the team and proposed we pivoted to something else.

Luckily, I had unknowingly teamed up with 4 incredibly talented people, who were surprisingly open-minded and willing to kill their babies when necessary. Unfazed by the rapidly approaching sprint deadline, we buried the camping idea and quickly started brainstorming the next one. This time, I pushed for a STEM-related topic, and so we began entertaining the new direction.

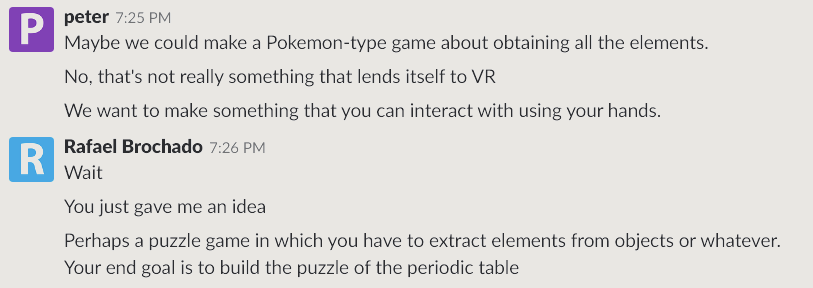

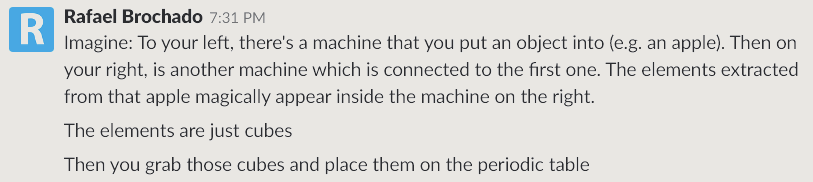

After tossing around a couple of bad ideas, this happened:

And thus Tablecraft was born.

I immediately got in-engine and started prototyping what the core experience should feel like. Fabiana and Titanya set out to construct a lab and craftable objects, while Quinn and Peter took on the role of programming the logic for our first machine: the “element extractor”. 🙌

Meanwhile, I was tasked with figuring out the big picture and making sure the overall experience was fun and engaging. My biggest concerns at the time were:

- How can we design the game around VR and the movement restrictions that come with it?

- Are we leveraging VR’s full potential? What sort of interactions can we have that are only possible in VR and not in real-life?

- What’s the tone of our game? Who are we trying to appeal to?

- How are we going to teach the core mechanics to the player? Can we do so in elegant ways that require no out-of-place UI elements floating around?

- How many chemical elements is the player gonna have access to right at the start of the game? What objects will the player be able to craft?

- How can we create a sense of progression?

- Do we have a proper fun/educational balance? How can we make a game that’s educational but also fun and appealing to players with no interest in chemistry?

After a couple of days of rapid iteration, things started shaping up:

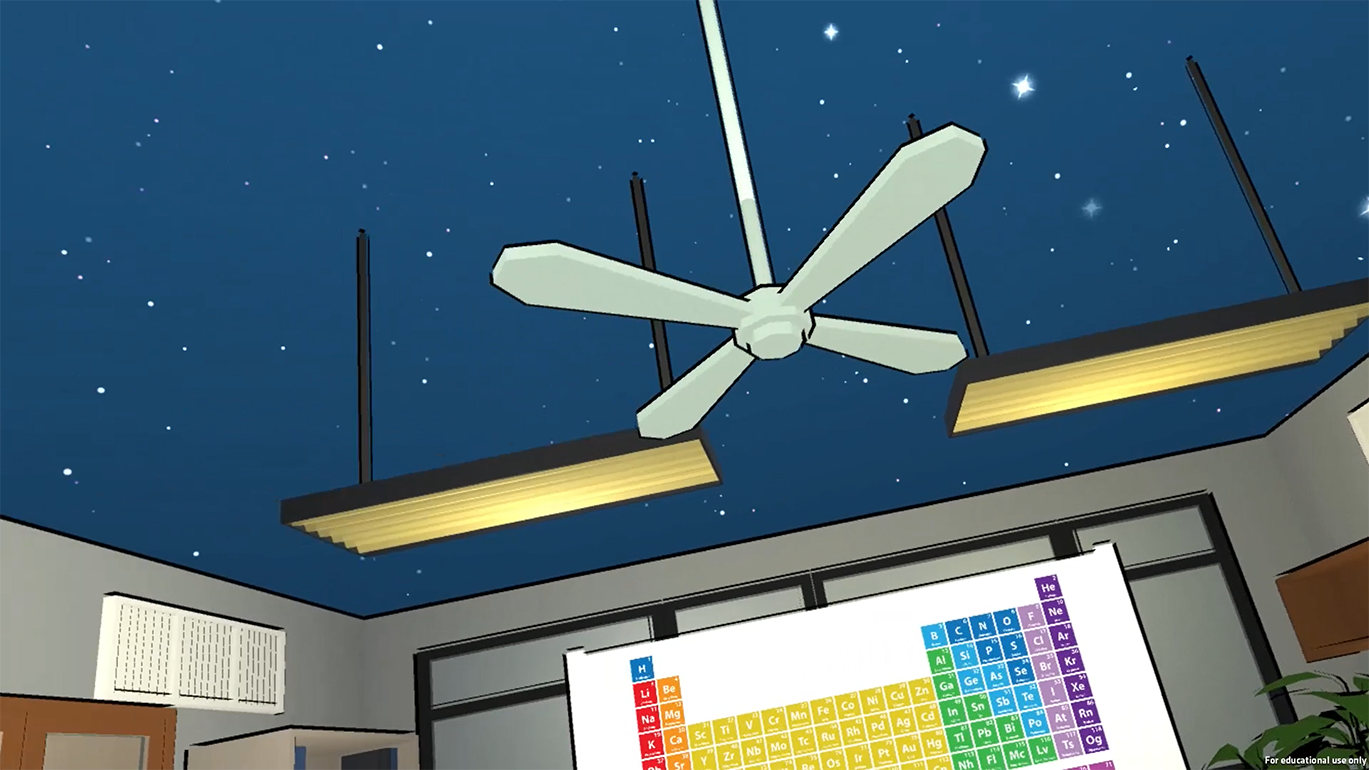

We added a secondary “database machine” where the formulas for all the craftable objects were now displayed, as well as a whiteboard with the periodic table right in front of the player. The whiteboard in particular was my first attempt at creating a sense of progression. The player started off with a certain amount of undiscovered elements, and by deconstructing objects present in the room, new elements would be discovered, thus allowing for the construction of new objects, and so on and so forth.

By the time the 2-week sprint had ended, this is what Tablecraft looked like:

We tackled the issue of VR movement by centralizing the majority of the action on the desks surrounding the player and giving them “magnetic” gloves (granted, at this point they’re just the default Oculus hands) that give them the ability to grab any object in the lab from a distance. The AI assistant – which at this point is just a voice – helps the player understand what is happening in the lab, but also acts to tutorialize systems, motivate the player towards faraway goals, and be a companion who is interested in the course of the player’s play.

In the pursuit of our tone, I noticed that the lab felt pretty dry and enclosed. It felt too much like a traditional classroom setting, which was the opposite of what I wanted it to feel like. So I ripped out the ceiling and replaced it with what I believed would be a much more engaging overhead view: the starry night sky. Now, perhaps that was just my excuse for inserting a little bit of my love for astronomy in Tablecraft, but nevertheless, I felt like it successfully set the tone just right for the play taking place in the lab itself. Stepping into the lab after that, I no longer felt like I was stepping into a classroom, but my own little world of the imagination instead, which not only felt like the right tone, but also exposed my mind to a wealth of new game design ideas. Ideas that I could not wait to explore.